Last week, on Halloween, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) posted an item on the “FDA in Brief” tab of the “FDA Newsroom” section of the agency’s website. This is generally the section where the FDA alerts us that it has provided a status update on a program, offered guidance on a topic or taken steps to advance an initiative. It’s usually not where information about food poisoning outbreaks appears. Outbreaks have their own section on the FDA website. But the Halloween post was about a food poisoning outbreak. One that was over and didn’t kill anyone but FDA was letting you know, it said, there in the “FDA in Brief” section, because, hey, transparency.

And that’s true. The FDA didn’t have to tell us about that outbreak. There are lots of food poisoning outbreaks that happen every year that we never know about.

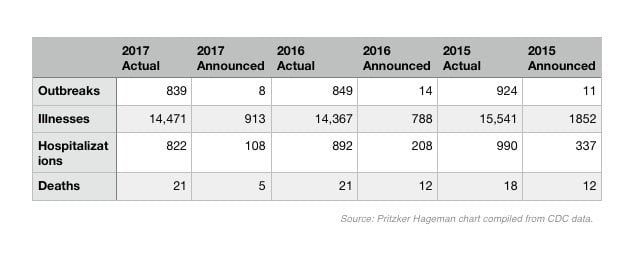

In 2017, there were 839 food poisoning outbreaks in the U.S., according to the most recent annual data on the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) website. These outbreaks sickened 14,471 people, hospitalizing 822 of them and killing 21. But that year, the CDC announced a total of eight outbreaks that sickened 913 people, hospitalizing 108 of them and killing five.

The 2017 actual v. announced outbreak numbers are pretty standard. In 2016, there were 849 actual outbreaks, 14 were announced. In 2015, there were 924 actual outbreaks and 11 were announced. And so on. Whenever the CDC announces an outbreak, the FDA or the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), depending on which food is involved, will usually publish a companion report or announcement.

It’s never been made clear how exactly the outbreaks that are announced get selected. It’s not, for example, if the outbreak involved a restaurant, the most common setting for a food poisoning outbreak. In 2017, 61 percent of the 839 outbreaks reported were linked to restaurant food but none of the eight announced outbreaks that year was specifically linked to a restaurant.

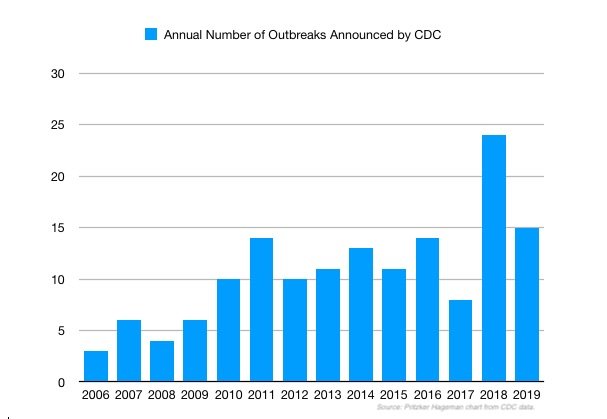

And it’s not if the outbreak was multi-state, which all announced outbreaks are. In 2017, there were 31 multi-state outbreaks, in 2016 there were 40.

And it’s not even just if the outbreak included fatalities. Most of the announced multi-state food poisoning outbreaks don’t include fatalities.

What is clear is that the public is made aware of a fraction of the food poisoning outbreaks that take place in the U.S. annually. And that there’s an unstated art to the science of that disclosure process.

Secret Outbreaks

Even the belated disclosure of an outbreak, like the one this year on Halloween, is not unusual. These pop up from time to time.

The Secret Caramel Apple Listeria Outbreak

For example, in February 2019, we learned that a second caramel apple Listeria outbreak occurred in 2017. The outbreak, which sickened three people, came three years after the first-known outbreak linked to caramel apples which sickened 35 people in 12 states killing seven of them.

All three of the 2017 caramel apple patients purchased pre-packaged caramel apples from a store the month before they got ill. Three retail locations sold the product, which was packaged in a plastic clamshell container holding three caramel apples, each on a stick.

Only one store still had the products for sale when health officials looked for samples to test. The Illinois Department of Public Health tested eight packages and none was positive for Listeria but “it is not known whether the tested caramel apples were from the same lots as those consumed by the ill persons in this outbreak,” the CDC stated.

The FDA inspected the caramel apple production facility, reviewed records and collected environmental samples for testing. The agency did not find any food safety concerns and none of the environmental swabs was positive for Listeria. “Traceback activities did not implicate a specific lot or supplier of whole apples used in brand A caramel apple production during the period of interest,” the report stated.

The Secret Ground Beef Salmonella Outbreak

In 2018, we learned about a Salmonella ground beef outbreak that took place in 2017. More than 100 people were sickened and one person was killed. The outbreak lasted 10 months before ending in July 2017. According to the USDA’s Food Safety and Inspection Service, the federal agency charged with protecting public health by ensuring the safety of meat, poultry, and processed egg products, the outbreak was not announced while it was ongoing because there was “no actionable information.” That means the outbreak went on for almost a year but they could not narrow things down enough to warn consumers about which meat might be tainted.

The Secret Cucumber Salmonella Outbreak

In 2015, we learned about a cucumber Salmonella outbreak that occurred the prior year. That outbreak lasted four months and sickened 275 people in 29 states. One person died.

Some of the people sickened said they had traveled to the Delmarva region (Delaware, Maryland, Virginia) before they developed symptoms. The outbreak strain Salmonella Newport JJPX01.0061 is novel to Delmarva. A traceback investigation for one cluster of illnesses, identified a common grower in Delmarva. That farm’s records indicated that poultry manure was applied approximately 120 days before harvest. During the investigation, the manure was not available for testing, and samples from the farm, which were taken months after harvest, did not test positive for Salmonella.

All three of the outbreaks mentioned above were revealed to the public in reports in a CDC publication called Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR). This next outbreak might also get a write-up there someday, but on Halloween, it appeared as a tidbit in the briefs section of the FDA website.

The Secret Romaine Lettuce E. coli Outbreak

The 2019 romaine lettuce E. coli outbreak sickened 23 people in 12 states, eleven of whom were hospitalized. The revelation came after back-to-back romaine lettuce E. coli outbreaks in 2018, neither of which was definitively resolved.

In the first 2018 romaine E. coli outbreak, 200 people got sick and five of them died. Investigators were not able to identify a common brand, farm, grower or supplier. But they did know the lettuce came from the growing region in Yuma, AZ. So, they warned consumers not to eat and restaurants and retailers not to sell romaine lettuce unless they knew it was grown elsewhere.

Chaos ensued as consumers discovered that most labels on romaine lettuce don’t state where it was grown. Then some stores issued recalls, some didn’t. Some restaurants stopped serving romaine, some didn’t. And some romaine producers issued statements saying: “It wasn’t us!”

When the second outbreak rolled around a few months later, the FDA and the CDC told consumers, retail stores and restaurants to throw away ALL romaine lettuce, outraging the entire industry. Then a few days later, the FDA said it had narrowed down the growing region to Central California and, again, advised consumers to avoid lettuce grown in that area. With bad label information, consumers were still at loss.

The 2019 romaine E. coli outbreak sickened people in a dozen states locate in different regions of the country. The case count reported by each state was: Arizona (3), California (8), Florida (1), Georgia (1), Illinois (2), Maryland (1), North Carolina (1), Nevada (1), New York (1), Oregon (1), Pennsylvania (2) and South Carolina (1).

The outbreak lasted from July 12, 2019 to Sept. 8, 2019, but the CDC didn’t find out about it until Sept. 17, 2019. After the CDC began its investigation, no more illness were reported. That doesn’t appear to be because of a recall as there is no public record of one available on the FDA website. So, it’s possible that by the time the CDC found out, the outbreak had run its course.

In its news brief about the outbreak, the FDA said the reason the FDA and CDC did not announce the outbreak was that there was no actionable information for consumers and that “the available data at the time indicated that the outbreak was not ongoing and romaine lettuce eaten by sick people was past its shelf life and no longer available for sale.”

Yet, through interviews with people sickened, the FDA had enough information about the brand names of lettuce and store names where the lettuce was purchased to identify which farms on California’s central coast were the origin of the lettuce in question.

After the two 2018 outbreaks, there was a lot of talk about best practices and improved record-keeping but, apparently, not much action. In the Halloween announcement, FDA Deputy Commissioner for Food Policy and Response Frank Yiannas said, “However, our investigation, along with previous outbreaks linked to romaine, reinforces the recommendations that we have made to the leafy green industry: producers must continue to review their practices and improve traceability to enhance food safety.”

But while we wait for that to happen, isn’t there some information that can be shared with consumers?

If a batch of Brand A lettuce/ground beef/caramel apples/cucumbers was contaminated with E. coli/Salmonella/Listeria and made a bunch of people sick, shouldn’t consumers know? Even if the tainted batch was off the market by the time the illnesses were discovered?

Food Safety Lawyer Fred Pritzker thinks so. “Consumers need this information so they can make informed choices,” said Pritzker, whose firm Pritzker Hageman has represented clients in almost every major food poisoning outbreak in the last 20 years. “If we have more transparency, we will have more accountability.”